6.7.5.5 Controlling the spread of disease

The global coronavirus pandemic highlighted the need for controlling the spread of disease, but there is disagreement on how best to do this

Plagues have been recorded throughout history, several of which have affected more than one country. The coronavirus pandemic of 2019 to 2023 is analysed here as an example of what can happen and political responses to it.

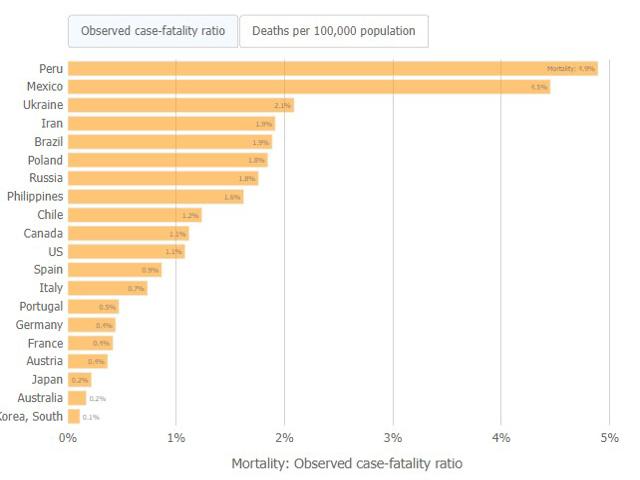

The World Health Organisation officially reported global deaths in the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic as 6.9 million by August 2023, “but the actual number is thought to be higher”. This resulted in a severe economic shock worldwide. The Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center published a chart showing numbers of deaths in relation to population size, which showed a wide variation between countries – with those at the top of the chart showing the highest death rates:

Ideally, governments aim to minimise early deaths and economic harm until pandemics

burn themselves out, but their political ideology affects their decision-making.

Authoritarian Populist Leaders

There is a strong correlation between authoritarian populism and high death rates in the coronavirus pandemic. Authoritarian populists, as described earlier (6.3.2.6), want to appear strong – and Donald Trump is a prime example. He was America’s President at the end of 2019, when the pandemic broke out, and several of the worst-affected countries on the above chart had such leaders at that time (although many other factors also affect death rates).

Trump initially tried to underplay the seriousness of the disease, likening it to flu. The BBC described his response in the first six weeks of the crisis: “he was on a determined mission to tell America that this thing from China was no biggie, and certainly was not going to upend the economy”. The article lists some of his pronouncements, including his claim almost six weeks after the start of the crisis: “The coronavirus is very much under control in the USA”. He refused to wear a face mask and his followers copied him – making the disease much harder to control. Death rates subsequently surged.

Politicisation of the coronavirus response

Joe Biden became President in January 2021, but Republicans reacted angrily against a Democrat government which introduced compulsory vaccination for some occupations to reduce the risk of unvaccinated workers infecting the public. The Economist reported that America’s pandemic is now an outlier in the rich world (which had a plentiful supply of vaccines) in September 2021:

“….Adjusting for population, the death rate is now about eight times higher in America than in the rest of the rich world.

“A slowdown in vaccinations in the country is largely to blame.

“….YouGov’s poll indicates that, among those who voted for Donald Trump in 2020, 31% say they will not get vaccinated, 71% strongly disapprove of President Joe Biden’s vaccine mandate and nearly 40% never wear a face mask.”

Government control of people's behaviour

Governments have constrained people’s individual liberty, to control the spread of the virus. It is unclear, though, to what extent applying the force of the law has been more effective than persuasion. Sweden had a lower death rate than Britain, even though it relied less on compulsion, as described by its chief epidemiologist.

Compulsory lockdowns, shutting businesses and preventing people from working, have been very costly in economic terms and in affecting the quality of people’s lives – especially for younger people whose education and careers have been put on hold. Pandemic decision-making, as described earlier on this website, is complicated by trying to remain popular. Politicians want to be seen to respond to the immediately visible deaths, which receive a lot of publicity in the short term, but less attention is paid to the long-term reduction in people’s quality of lives and their early deaths: which might be the effects of stress, deprivation, or the delayed treatment of other diseases.

Lockdowns reduce the number of deaths in the short term, but they cannot be left in place indefinitely. A BBC report, Most rules set to end in England, says PM, described the political balancing act of releasing lockdown in July 2021: “Unlocking was always going to drive up infections. And the problem with trying to delay that is the risk of a surge in cases at a much worse time.”

The World Health Organisation

The role of the World Health Organisation (WHO) in controlling the spread of disease has been contentious. It has been accused of bending to political pressure from China, for example. It has provided expert advice to every country in the world, and it has helped to distribute vaccines to poor countries through the COVAX scheme, but it relies on voluntary contributions from governments.

WHO has the organisational structure and resources to deal with future pandemics, and it is hard to envisage a better way of coordinating an international response.

Living with pandemics

As described in the Economist article, How the world learns to live with covid-19, “in the end, all pandemics burn out. Eventually, sufficient numbers of people develop immunity so viruses can no longer find new hosts at the rate they need to sustain their growth.” People gain immunity either through infection or vaccination – and the latter is much safer.

The ‘new normal’ for living with COVID-19 will be when it is endemic: always present, always killing some vulnerable people who might otherwise have died from a different malady, but not requiring harsh restrictions on most people’s behaviour. Governments need to avoid letting health services be swamped, though, so some caution will continue to be necessary.

Risk reduction

Older people are more likely to die from COVID-19 than those who are younger. Experts disagree about the best way of controlling the spread of disease: whether it is possible to protect the old whilst letting the young have more freedom, for example.

Politicians have claimed to be guided by science, although in practice they must make a judgement about whether people will comply with any regulations that are introduced. Vaccination has been very successful in reducing the number of deaths, but questions have been raised as to whether it can be or should be compulsory.

Risk reduction is a series of options, including some mandatory mask-wearing, encouraging working from home, allowing vaccine mandates, and using health passes at crowded venues. Politicians, guided by expert advice, must choose which measures to impose at any moment – but the experts don’t always agree, as illustrated by two contrasting articles that were published within 3 days of each other in October 2021:

A Guardian article, UK faces ‘another lockdown Christmas if we don’t act soon’, reported on calls for action to be taken swiftly to avoid much tougher COVID restrictions later.

The BBC report, Covid: Are cases about to plummet without Plan B?, notes that some experts were predicting a fall in infection rates for other reasons – without the need for the restrictive measures referred to as ‘Plan B’.

Future pandemics

They should be combated by immediately restricting international travel and advising the population to avoid risky behaviour until a vaccine can be developed. Political leaders should act swiftly and decisively, leading by example. And devolved decision-making is also essential – to avoid the blistering rage of northern leaders in the UK, for example, when local circumstances had not been taken into account.

(This is an archive of a page intended to form part of Edition 4 of the Patterns of Power series of books. The latest versions are at book contents).