7.2.7.1 Joining a Major International Alliance in a Multipolar World

Countries can protect themselves by joining a major international alliance, such as NATO or the SCO, for mutual support against threats

NATO

America, Britain, France, and nine other Western democracies formed the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) by signing a treaty in 1949, for mutual protection against the threat of communist domination. Its defensive role is shown in two excerpts from the NATO treaty:

Article 3: “In order more effectively to achieve the objectives of this Treaty, the Parties, separately and jointly, by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid, will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.”

Article 5: “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all…”

The treaty Preamble starts with the statement that “The Parties to this Treaty reaffirm their faith in the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments”. Some NATO members have nonetheless used military force without UN approval several times, including the invasion of Iraq as described in the next chapter.

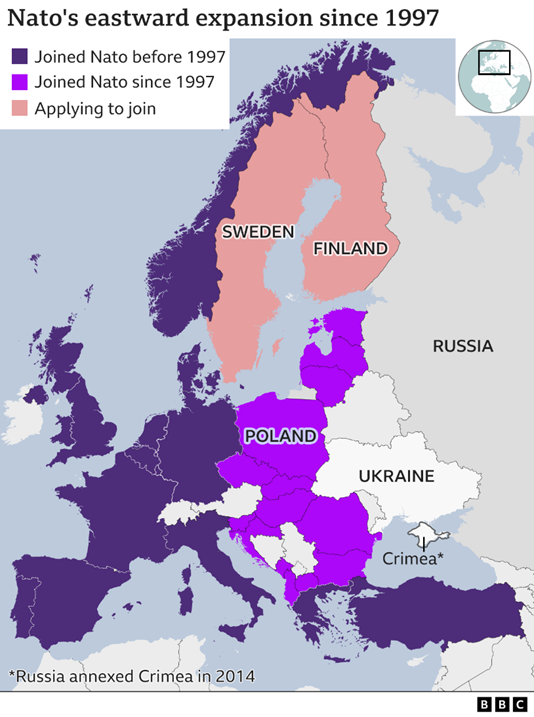

NATO did not disband at the end of the Cold War in 1989, and it has been expanding steadily eastward.

A BBC analysis,

published on the anniversary of Russia's

invasion of Ukraine, noted that “[b]laming Nato's expansion eastwards is a

Russian narrative that has gained some ground in Europe. Before the war,

President Putin demanded Nato turn the clock back to 1997 and remove its forces

and military infrastructure from Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the

Baltics.”

A BBC analysis,

published on the anniversary of Russia's

invasion of Ukraine, noted that “[b]laming Nato's expansion eastwards is a

Russian narrative that has gained some ground in Europe. Before the war,

President Putin demanded Nato turn the clock back to 1997 and remove its forces

and military infrastructure from Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the

Baltics.”

Whether or not Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was to stop NATO expansion, he has undoubtedly used that narrative to motivate his forces – persuading the Russian people that they are under threat. His anniversary speech to the Federal Assembly included these words: “We are defending human lives and our common home, while the West seeks unlimited power. It has already spent over $150 billion on helping and arming the Kiev regime.”

But Finland and Sweden have now joined NATO. As noted in the BBC analysis, they did this for self-protection in response to Russia's attack on Ukraine.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)

China, Russia and three ex-USSR states on Russia's southern border formed the Shanghai Five on 26 April 1996, to resolve border disputes and increase their mutual security, although analysis from Brookings suggested that it could also be characterised as “An Attempt to Counter U.S. Influence in Asia”. That group expanded, with the addition of Uzbekistan in 2001, to form the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) with “a new democratic, fair and rational international political and economic international order” as an aim.

The founding of the SCO followed NATO’s use of force in Yugoslavia to protect Kosovo in 1999, which was without prior UN authorisation, illustrating the Limits of International Law. That Kosovo intervention had unintended side-effects, as described later (7.3.2.2). It was seen as a clear signal that America and NATO would ignore international law if they found it convenient to do so. Russia and China were made angry by it.

The SCO has continued to expand – having 10 members by July 2024, including India, Pakistan, and Iran. The Joint communiqué after the 21st SCO meeting in 2022 affirmed the members’ commitment to “a democratic, fair and multipolar international order”. It is primarily an economic and political organisation, trying to change the geopolitical map of the world. And its use of the term “multipolar” indicates that it will not accept being pushed around by American power.

Vladimir Putin regards NATO's eastward expansion as an existential threat to his regime. There are two narratives to explain this. One might be described as a Western interpretation, and the other is Putin’s message for public consumption:

· The end of the Cold War was partly triggered by East Germans looking across the Berlin Wall and seeing freedom and prosperity on the other side. Several Eastern European countries, such as Poland and Czechoslovakia which were previously part of the USSR, have also become prosperous democracies. A pro-democracy movement in Russia would threaten Putin’s government.

· Putin’s article, On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, argued that Ukraine is intrinsically Russian, with “close cultural, spiritual and economic ties”. He argued that the links between the two countries were undermined as “the result of deliberate efforts by those forces that have always sought to undermine our unity”. He ignores the commitment that Russia made in the Budapest memorandum in 1994, “to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine” and “to refrain from the threat or use of force” against the country. He now positions the invasion as an attempt to rescue the Russian-speaking population of eastern Ukraine.

China has recently been antagonised by recent anti-Chinese rhetoric and economic sanctions against it. Trump's U.S.-China transformation included “tariffs on billions of dollars of Chinese goods, sparking a trade war that stretches on for most of Trump's presidency”. These have not been reversed by the Biden Administration and the anti-Chinese rhetoric continues. As the legitimacy of the Chinese regime depends largely on delivering economic growth (6.3.1.7), any threat to its economy is a threat to the leadership. And criticism of its government also undermines its legitimacy.

China and Russia have different reasons for seeing America and NATO as a threat to their power, but they both see the value of supporting each other. And trading partners are very important in a war: for the supply of weapons and technology, and to combat the economic sanctions that the West has used to put pressure on those who oppose its interests. These economic considerations explain why countries as different as India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Iran have been drawn into the SCO's sphere of influence. And, under the headline China's leader Xi in Moscow for meeting with Putin, that trip was reported as “a three-day visit that shows off Beijing’s new diplomatic swagger and offers a welcome political lift for Russian President Vladimir Putin”. It was probably intended to send a strong signal to the West that Russia can continue to rely on China's support.

The SCO is a very loose alliance, whose individual members have conflicting interests, but it is nonetheless important to all of them. It is having, and may continue to have, a big influence on the future of Russia's war with Ukraine:

· Members’ purchases of Russian oil and gas have largely neutralised an important element of Western strategy. The Russian economy is holding up against Western sanctions: “Moscow's GDP contracted by only 2.1% in 2022, according to the Russian statistics service Rosstat. The Russian economy is even projected to grow by 0.3% in 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF)”.

· Any decision by China to supply Russia with weapons and/or ammunition would decisively change the course of the war. NBC News reported that Russian troops 'forced to fight with shovels' as ammo shortage undermines Bakhmut advance, for example: “Russia’s positions in the area could be in jeopardy if the supply issues weren’t resolved”.

· China might be able to act as a peacemaker. A Reuters article, Can China broker peace between Russia and Ukraine?, points out that it has leverage over both parties: “China is Russia's most important ally”; and Ukraine “would not want to torpedo the chances of Chinese support for its reconstruction …[and] does not want to provoke China so much that they start arming Russia”.

· With lavish treatment of Macron, China's Xi woos France to "counter" U.S., according to a Reuters report on a State visit in April 2023, “which some analysts see as a sign of Beijing's growing offensive to woo key allies within the European Union to counter the United States”. Sowing division in Western unity is a way of weakening American influence.

Comparing the major international alliances

Although both NATO and the SCO claim to support international law (5.3.6), they have made their own security arrangements. They are two major international alliances with opposing strategic aims and different structures.

NATO's military capability is unsurpassable for the foreseeable future, and all its members are committed to defending any that are under military threat. Deliveries of ammunition and weapons to Ukraine, a non-member, are dependent on goodwill though – and that might change. The US Presidential election in 2024 could affect American support, as Republican candidate Ron DeSantis has said that “Further U.S. involvement in Ukraine is not [a] vital national interest”.

The SCO is dealing with Russia on a commercial basis, which is a completely different model. Its support could continue indefinitely. It is a much looser alliance than NATO, without a commitment to defend its members, but the support that it does offer might be more reliable in the Ukraine situation.

Another international alliance, the African Union, describes itself as “a continental body consisting of the 55 member states that make up the countries of the African Continent. It was officially launched in 2002 as a successor to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU, 1963-1999).” It declares its aims as “An Integrated, Prosperous and Peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena”. It is less fully developed than NATO or the SCO as a form of self-protection for member States, although it has contributed forces for UN peacekeeping.

(This is an archive of a page intended to form part of Edition 4 of the Patterns of Power series of books. The latest versions are at book contents).